Group

Group

Print & Fly

The dream of flight has moved on a level. Today, it revolves around producing a complete aircraft using a 3D printer. That stage has not yet been reached. However, a team of researchers at Liebherr is gradually getting closer to achieving this dream.

Layered for posterity

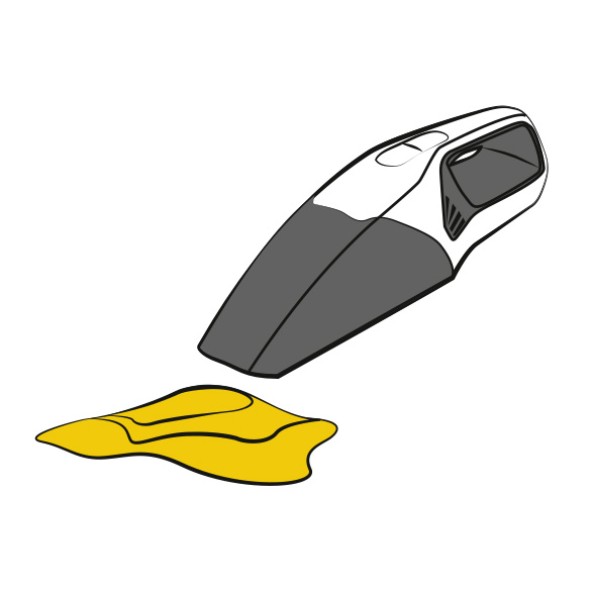

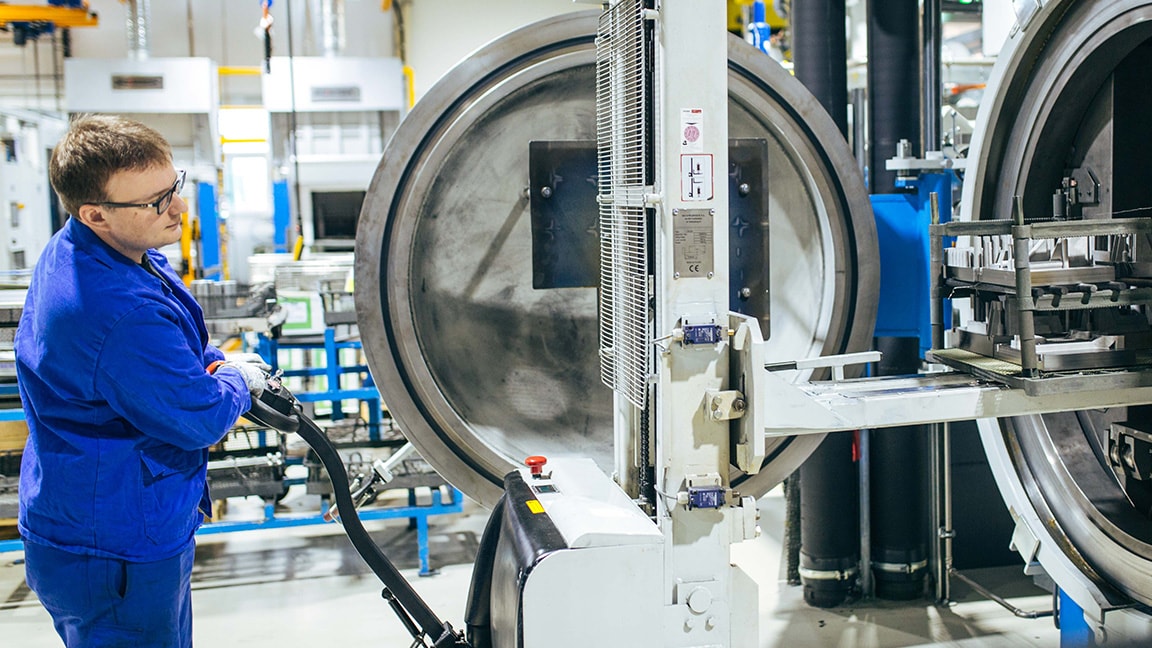

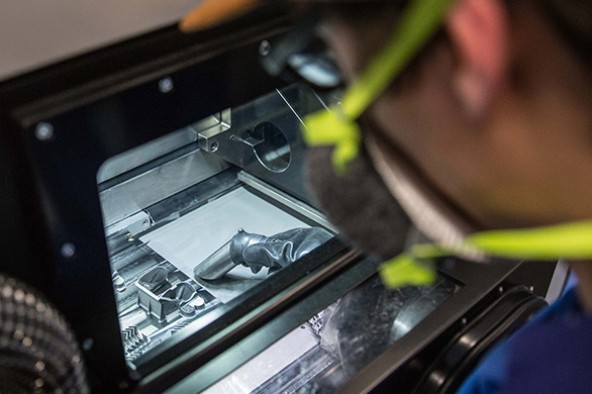

"I would never have thought that I would enjoy vacuum cleaning so much," says Adrian Führer, attaching the hose of the suction device to the machine. He taps the touchscreen. The device hums into action. Through the observation window, he watches his creation emerge from the grey dust. "It is always a great moment when the component is revealed in its full glory," he says. The industrial mechanic is responsible for the 3D printer at Liebherr-Aerospace: he sets it up for print jobs, fills it with titanium powder, prepares the laser for the computer-controlled melting of the material – and, last but not least, vacuums up the excess titanium powder. "I find 3D printing amazingly exciting. When I was asked if I wanted to work with the research team, I didn't have to think twice. I said yes straight away," says Adrian Führer.

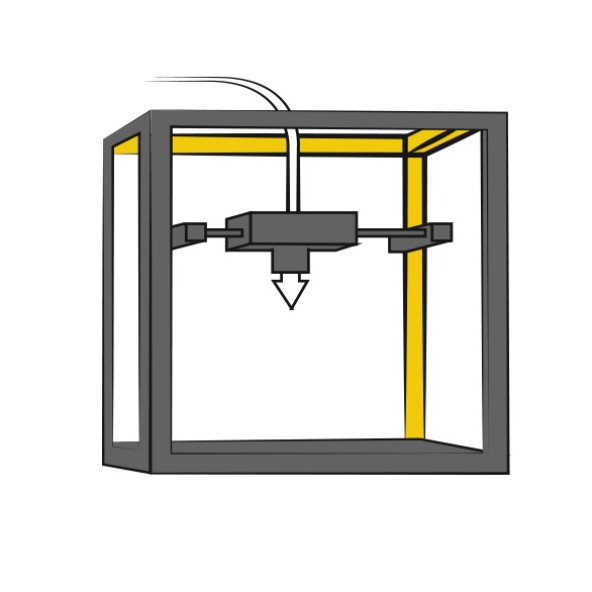

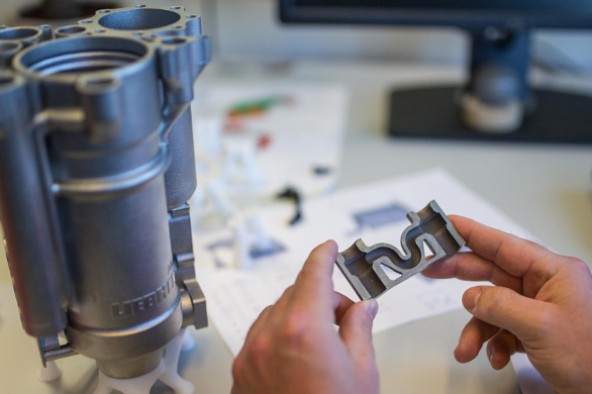

In the Liebherr factory in Lindenberg, the 3D printer is located centrally between production, dispatch and assembly. In a production area surrounded by glass walls, at the centre of which stands the computer-controlled printing machine, which is taller than a person. A live transmission of what is currently happening in the printer is shown on a large monitor. Employees and visitors walking past frequently stop to take a look at the future of industrial production technology. In front of the printer stands a highly polished titanium component for an Airbus A320. "Funded by the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy" reads the label.

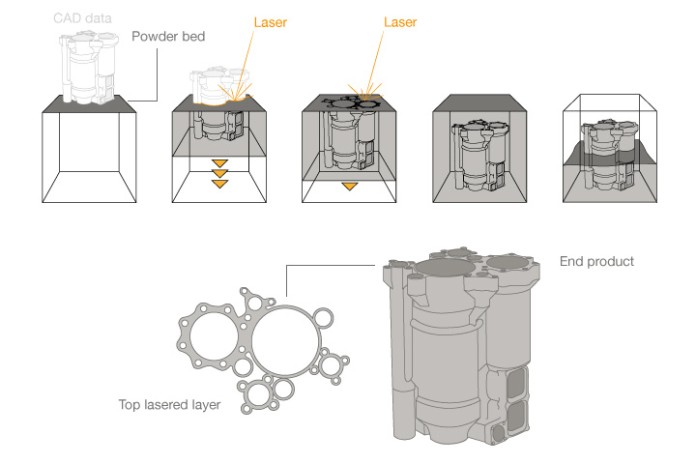

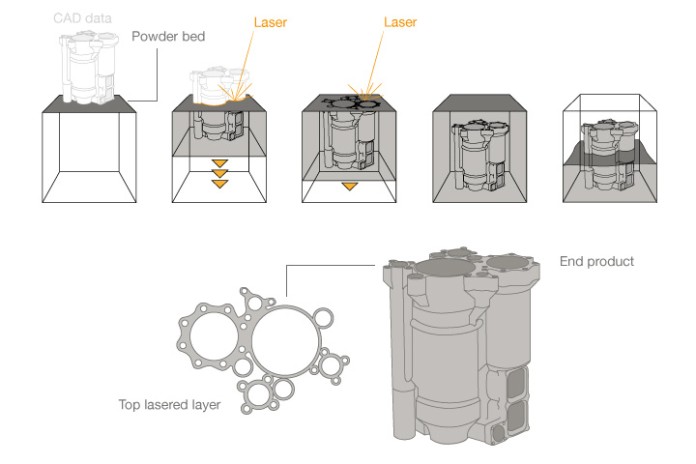

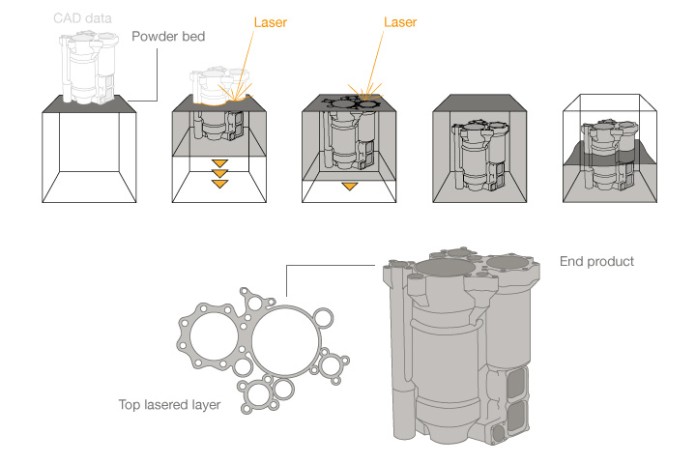

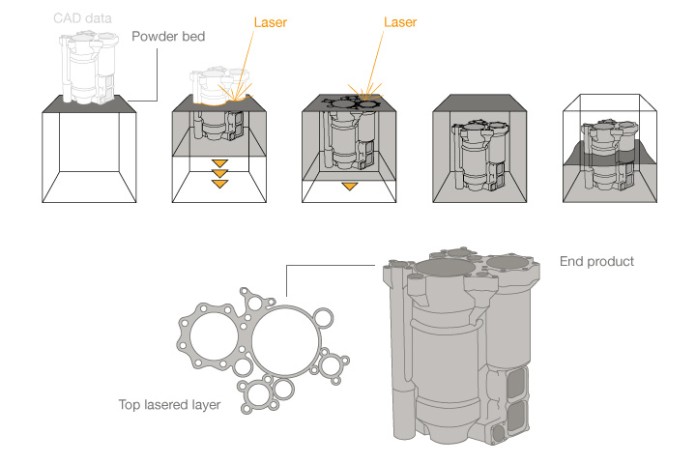

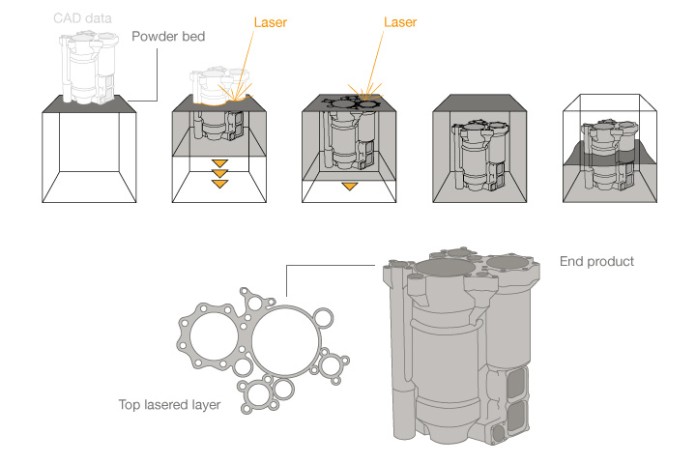

Adrian Führer talks about his work with great enthusiasm. "The printer builds up a component from a large number of thin titanium layers, each just 30 to 60 micrometres thick," he says. "The laser travels across the titanium powder, following a design model precisely, and melts it down with millimetre precision using a blinding point of light. In this way, the component gradually takes form from the bottom up." The printer requires about 20 hours to print a valve block which will accommodate a maze of cables and pipes and can be used to control an aircraft's landing flap.

The future of 3D printing

3D printing – the future emerging from the laser melter

Additive manufacturing is the name given to a process which uses digital 3D design data to build up a component layer-by-layer by melting material. The term "3D printing" is used more and more often as a synonym for additive manufacturing. However, additive manufacturing is a better description, indicating that the process involved is a professional production process which differs significantly from conventional subtractive manufacturing methods. Instead of milling a part from a solid block, for example, additive manufacturing builds up components layer by layer from materials which come in fine-powder form. Materials available include a variety of different metals, plastics and composites.

One of the areas in which this manufacturing method is used is that of rapid prototyping, the construction of illustrative and functional prototypes. Product development and market launch times can be shortened significantly by this method. Additive manufacturing is now increasingly being adopted in series production. It opens up opportunities for large OEM manufacturers from a wide range of industries to differentiate themselves in the marketplace – in terms of new customer benefits, potential cost savings and achieving sustainability targets.

CAD data

Find out more

Laser

Find out more

Powder

Find out more

Suction

Find out more

Working in tandem with evolution

The castors on Johannes Walter's office chair have proved a worthwhile investment. He is forever pushing off with his foot and gliding the two metres over to Stefan Hermann. The two sit back to back in the office and at the moment they have a lot to discuss. Stefan Hermann is a simulation engineer. On his screen, he has an image of a complex mesh structure. "This is something that evolution came up with," he says. "The structure is modelled on a tree root. The branching structure of the root always produces the right balance between resource use, strength and sustenance for the tree. What evolution needed millions of years for, we were able to do using a computer, designing a lightweight joint for an aircraft landing gear component based on the same principle of optimisation," explains Hermann.

This is another reason Johannes Walter has moved across to him. The designer is playing a creative one-two with the simulation engineer. From Hermann's calculations, Walter creates a shape which will ultimately be integrated in the landing gear. On his computer, the component he has constructed looks like a crescent moon, the surface of which is full of holes like a Swiss cheese. "This saves on material and weight," says Walter, "and uses the strength structures calculated as being optimal." Almost any shape can thus be represented in CAD and then, using 3D printing, produced exactly as required by the developers for the target function.

The two inventors are part of a six-person team led by Alexander Altmann, head of the Additive Manufacturing / Research & Technology project, which Liebherr launched six years ago in Lindenberg. "3D printing is a technology that is over 20 years old, but has recently experienced an enormous boom and offers exciting prospects, particularly in aircraft engineering," says Altmann. “Airbus recently flew on of our 3D printed spoiler actuator valve blocks on a flight test A380. The first-ever 3D printed primary flight control hydraulic component flown on an Airbus aircraft! The valve block offers the same performance as the conventional valve block made from a titanium forging, but it is 35% lighter in weight.”

Since the demands on aircraft components are extremely high, he and his team are primarily concerned with understanding additive manufacturing methods down to the last detail and setting up absolutely reliable production processes. "To this end, we measure and document every step, however small, in the construction of the component. Errors are not an option. There must not be even the slightest doubt as to the reliability and safety of the components and the material from which they are made."

By clicking on “ACCEPT”, you consent to the data transmission to Google for this video pursuant to Art. 6 para. 1 point a GDPR. If you do not want to consent to each YouTube video individually in the future and want to be able to load them without this blocker, you can also select “Always accept YouTube videos” and thus also consent to the respectively associated data transmissions to Google for all other YouTube videos that you will access on our website in the future.

You can withdraw given consents at any time with effect for the future and thus prevent the further transmission of your data by deselecting the respective service under “Miscellaneous services (optional)” in the settings (later also accessible via the “Privacy Settings” in the footer of our website).

For further information, please refer to our Data Protection Declaration and the Google Privacy Policy.*Google Ireland Limited, Gordon House, Barrow Street, Dublin 4, Ireland; parent company: Google LLC, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, USA** Note: The data transfer to the USA associated with the data transmission to Google takes place on the basis of the European Commission’s adequacy decision of 10 July 2023 (EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework).

Excited about the future

Alexander Altmann's team has convened for a regular meeting in the conference room. André Danzig has only been in the team for a year and a half. Nonetheless, the PhD physicist is already a kind of "veteran" of additive manufacturing. Before he came to Lindenberg, he worked for a 3D printer manufacturer for over 15 years. Then one day he decided he wanted to find out more about the user side. "What does simulation tell us? How can we achieve design stability if we print not only the individual components but the entire control element, integrating all the functions at the same time?" Danzig wants to know. Stefan Hermann has already calculated all that and has also shared his ideas about it with the designer. "We will definitely achieve it," says Hermann, presenting the relevant considerations to the team.

By clicking on “ACCEPT”, you consent to the data transmission to Google for this video pursuant to Art. 6 para. 1 point a GDPR. If you do not want to consent to each YouTube video individually in the future and want to be able to load them without this blocker, you can also select “Always accept YouTube videos” and thus also consent to the respectively associated data transmissions to Google for all other YouTube videos that you will access on our website in the future.

You can withdraw given consents at any time with effect for the future and thus prevent the further transmission of your data by deselecting the respective service under “Miscellaneous services (optional)” in the settings (later also accessible via the “Privacy Settings” in the footer of our website).

For further information, please refer to our Data Protection Declaration and the Google Privacy Policy.*Google Ireland Limited, Gordon House, Barrow Street, Dublin 4, Ireland; parent company: Google LLC, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, USA** Note: The data transfer to the USA associated with the data transmission to Google takes place on the basis of the European Commission’s adequacy decision of 10 July 2023 (EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework).

Alexander Altmann likes the idea that: "3D printing will fundamentally change not only aircraft components and entire aircraft structures, but also other products such as cars and toys. It will even be possible to produce foods and medical implants. I am sure that its impact over the next 20 years will be huge."