7 minutes - magazine 01 | 2025

Pretty wild times

Today, sanctions against Russia prevent the direct transport of cranes from Ehingen to Central Asia. Dilapidated bridges force unnecessary detours during transports across Europe. Bureaucracy and the time required to apply for transport licences further complicate crane transfers.

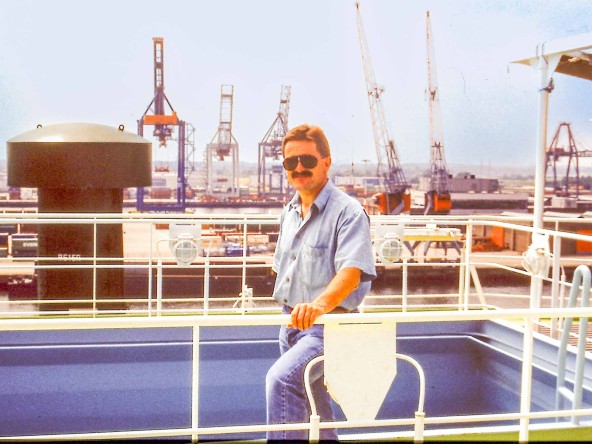

Was everything better in the past? Certainly not. Only different. We asked our former shipping manager Bruno Seele, company founder Josef Gerber from the transfer company of the same name and driver Heinz Zobel to tell us about crane transports to Iraq, Mauritania and the former Soviet Union. Here are a few anecdotes for you to enjoy.

Adventure into the unknown

Bruno Seele (left in the picture next to Josef Gerber): “Then as now, transporting our mobile cranes mainly involved high-capacity and heavy-duty transport operations with a wide variety of challenges depending on the transit countries, destination, seasonal influences, infrastructure conditions and a multitude of legal regulations as well as political influences. These are not off-the-peg transports, but often journeys that feel like grand adventures, where the script is only fully written in hindsight.”

Never run out of petrol!

Josef Gerber: “One customer had a bad experience in the Mauritanian port of Nouadhibou – the crane had fallen off the ship into the quay wall during the lift. He didn’t want to risk it a second time. Instead, the crane was transported overland on a 3,700-kilometre route from Casablanca, through the Sahara and Sahel regions, to a mine in Mauritania. We needed 3,500 litres of diesel for this drive. The problem was that petrol stations were scarce – and sometimes there was no diesel. Whether headed to Mauritania or other exotic destinations, we always had extra 80-litre canisters with us and filled the crane to the brim wherever possible.”

Eat my dust

Josef Gerber: “At the border crossing from Western Sahara to Mauritania, the road was covered in sand. To stay in the right tracks, I followed two lorries ahead of me – for 80 kilometres. When you’re driving a crane out there, the traffic behind you can’t see anything at all. And if you drop below a certain speed, you can’t see anything either, because the desert dust overtakes you.”

Good relations

Josef Gerber: “Depending on the country, customs clearance during transit sometimes took two to three days. It was tough enough for the drivers, but standing around in the heat made it even worse. Most of the time, the journey continued after half a day, but if the border officials suddenly decided that a new form had to be completed – one we knew nothing about – that’s when the trouble began. Having good connections over the years was crucial and helped speed up the process.”

Better travelling in a group

Josef Gerber: “The return journey from Mauritania to Germany was almost as time-consuming than the crane transport itself. As the risk of terrorism in the country was high and booking a flight from Nouakchott was very difficult, I didn’t fly back to Germany alone. It was safer to return to Morocco first with the escort vehicle and the Moroccan lorry drivers, who were familiar with the local conditions. Only once there did I board a plane home.”

Carpe diem

Heinz Zobel: “There are no delineators in the desert. Animals roam freely, carts and pedestrians travel without lights. That’s why we only drove during the day. On one stretch, we once counted 44 dead donkeys.”

Heating for the diesel

Josef Gerber: “Whether crossing the Alpine passes to Italy or through the Carpathians, we were often travelling in wintry conditions. During the Cold War, a total of 16 cranes were shipped to Siberia under a special licence to build gas pipelines. To ensure the cranes could function at temperatures as low as -40°C, the fuel lines were fitted with heating wires to allow the engine to start. The tyres, however, posed a bigger challenge. The all-terrain cranes had lug tyres that were not designed for continuous speeds. Between Göttingen and Hamburg the route was flat and you could travel at a constant 70 to 80 km / h. This caused the outer casing of the special tyres to become detached from the inner casing after long drives.”

Bruno Seele: “Our customer service team reacted quickly. Overnight we dispatched replacement tyres to the convoy by lorry. At the same time, we collaborated with the tyre manufacturer to find a solution: regular breaks for the cranes en route to the port to allow the tyres to cool. Despite these challenges, the cranes arrived on the ship on time.”

Nailed down

Heinz Zobel: “The crane operator’s cabs were particularly vulnerable parts of the cranes. During transport on Russian railways, branches would often obstruct the route and occasionally strike the windows. To prevent any damage, the cabs were covered with wooden cladding – including a peephole, so the crane could still be manoeuvred, for example, onto a transport ship. The cladding had the additional advantage that it provided good protection against theft – the side mirrors and lights were popular targets in many countries, and on one occasion, we even had an entire axle stolen.”

With hands and feet

Heinz Zobel: “At some point, even speaking English doesn’t get you anywhere. In those situations, we communicated using hands and gestures, and somehow it always worked out. You couldn’t just give up when things became difficult. As with so many challenges ‘on the road’, it was also important to keep calm when it came to communication.”

Bruno Seele: “What also helped in difficult situations were the strong connections we had in each country – be it the customers themselves, our global service companies or internationally operating service providers, whose local branches and staff were always there to support us.”

Cash is king

Josef Gerber: “Almost everywhere we transported cranes, we always took enough money with us in local currency – otherwise you wouldn’t get very far. One exception was Iraq, where everything had to be paid for in dollars. One particularly nerve-wracking experience was the return transport of twelve cranes from Odessa to Germany. The transit costs in Bulgaria, i.e. the deposit to ensure that the cranes leave the country again after travelling through, had to be paid or deposited in cash. To remain as inconspicuous as possible, my wife Marianne sewed a six-figure amount in Deutsche Marks into the lining of an anorak – a movie-worthy adventure.”

An adventure every time

Bruno Seele: “Since I started working in dispatch at Liebherr in 1976, I’ve always placed great importance on having reliable partners and working with internationally oriented service providers who were represented locally. Direct contact was always a priority for me: I didn’t just want to talk to a representative from Stuttgart or Frankfurt, but also to the people from Baghdad, for example. This approach gave me a strong sense of the challenges and local nuances along each transport route. That intuition helped me make the right decisions.”

This article was published in the UpLoad magazine 01 | 2025.